Knife in the Water (1963)

On their way to an afternoon on the lake, husband and wife Andrzej and Krystyna nearly run over a young hitchhiker. Inviting the young man onto the boat with them, Andrzej begins to subtly torment him; the hitchhiker responds by making overtures toward Krystyna. When the hitchhiker is accidentally knocked overboard, the husband's panic results in unexpected consequences.

Watch Trailer

Cast

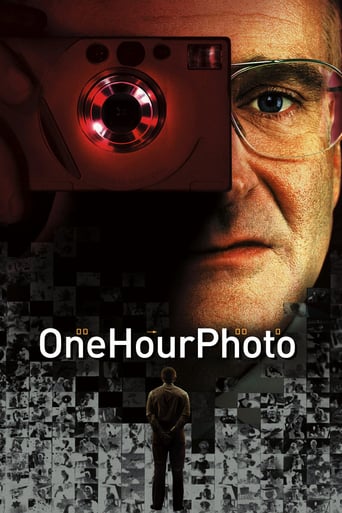

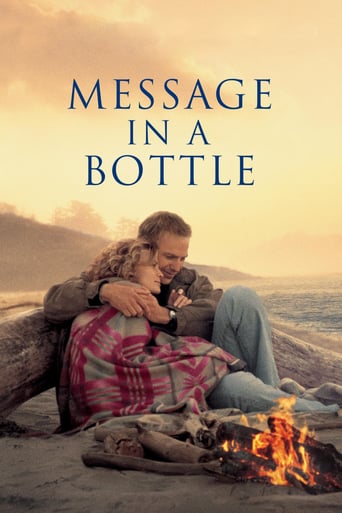

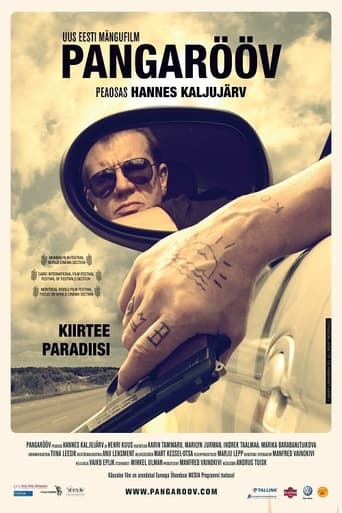

Similar titles

Reviews

Sorry, this movie sucks

Good movie, but best of all time? Hardly . . .

A great movie, one of the best of this year. There was a bit of confusion at one point in the plot, but nothing serious.

By the time the dramatic fireworks start popping off, each one feels earned.

The movie is a brilliant psychological thriller. It tells a story of limited space and intense circumstances. The story is simple cause there are only 3 people in the middle of the sea during the whole movie. But emotions and actions of characters are profound. Only three characters, confined on a boat together for most of the run time – come from is felt throughout, most notably in the concept of materially. Upper-class, middle-aged Andrzej clings tightly to his yacht, his pride and joy and central symbol of bourgeois decadence and power, while the hitchhiker, although assembly hailing from a 'lower' social class. The obsession over materially and pride is a major part of what brings the characters to blows later on, and is of course fundamental to their aggressive instincts. This movie was examining the relationship between men and women in the primitive level. When a young hitchhiker joins a couple on a weekend yacht trip, psychological warfare breaks out as the two men compete for the woman's attention. "If two men are on board, one is the skipper." The struggle between the men in the movie, it's based upon this sentence. Both men were trying to prove themselves. It was like woman has to choose one of them in the end. For the reasons knife which is a primitive weapon was turning the power object. The knife not merely as a sign of virility, but also as a metaphor for psychological force in the duel between the two men for the attentions of the woman. Polanski creates a disturbing study of fear, humiliation, sexuality, and aggression with only there people. On the first point, the sexual 'contest' between Andrzej and the Hitchhiker over Christine is clearly the most significant source of aggression in the film. It is also one of the ideas that, as much time as the film spends exploring and depicting it, is hardest to nail down or explain in a reasoned, ordered fashion. Why does Andrzej need to feel so threatened by the Hitchhiker as to become outright aggressive? Of course – the Hitchhiker's youth and virility, Andrzej's materialistic possessive behavior towards his wife, etc. – but none of them completely summarize the issue. There is something highly emotional, and highly animistic, about Andrzej's feeling of sexual threat, and it is something I cannot completely understand One of the things that makes the film thriller film outside of the characters that the whole movie is in the middle of the sea. There is nowhere to escape, disconnected from the world around them. The characters are entirely isolated. It is only in this geographical isolation that Andrzej and the Hitchhiker allow their aggression to come out in full, and it is telling that once Andrzej returns to land, and becomes 'un-isolated,' he comes to his senses and feels moral shame for his aggressive actions. The movie try to understand the sources and contexts of aggression in intellectual, ordered ways, they are ultimately studies of the mysterious emotional state that is aggression itself, of the universal human struggles, senseless forms violence takes when stemming from such dense and complicated emotional issues. Knife which is one of the most important figures in the and which is the symbol of manhood movie drowned in the waters of the sea. And everyone's pride is bruised. The movie ends in an interesting way. At this point the woman has a confession to Andrzej. But Andrzej doesn't believe in it. Whether or not he has lost in both cases. I think the only winner of the film is young man. He continues to survive without considering any result.

Roman Polanski's well-acclaimed feature debut, is the only film he has made in his native country Poland. KNIFE IN THE WATER is an intelligent drama exclusively resolves around three people, Andrzej (Niemczyk), his wife Krystyna (Umecka) and an unnamed young man (Malanowicz) with minimal locations.Middle-aged Andrzej, driving with his much younger wife Krystyna on their way to a daily sailing, en route, Andrzej almost knocks off a reckless hitchhiker, outraged, he still agrees to take the stranger, and eventually invites him to join them together for the excursion, here, Polanski hints the motivation, since the young man claims he doesn't have the faintest about sailing and cannot swim at all, as a man twice of his age, Andrzej's intention to teach him some hard lessons and make himself look good (an ego boost is very much needed because things are not very smooth between him and Krystyna as well) is quite obvious.The journey starts in a predicted direction, Andrzej is the self-claimed captain, as if he were a seasoned seafarer, instructs the young man with basic nautical techniques, teases him for his clumsiness, and gets offended when his yarn turns out to be a bore to his guest. The tension between the two men (two generations) is tangible, but out of courtesy and etiquette, it has been buried underneath the surface, there is even a peaceful period when all of them hide inside the sailing boat and spend a night during an unexpected tempest. The next day, what triggers the falling-out is actually very understated, but a sensitive soul may sense Andrzej's jealousy when he wakes up and finds out both Krystyna and the young man have already been staying outside, there is no inappropriate behaviours between them (as far as what Polanski shows us), but the insecurity of his sexual competence (especially facing the competition of a young man's hormones) pesters him even subconsciously, and soon it evolves into a battle of egos.From the young man's angle, he is not a wide-eyed simpleton, before accepting the invitation, he already betrays his complacency by saying that "he knows Andrzej will ask him to go with them", what does it mean? He is astute enough to predict Andrzej's motivation and is willing to take the challenge, with the fringe benefit of experiencing the middle-class luxury. Considering the time of the Communist Poland, it is an invitation rather tempting for a homeless youngster, but his rebellious nature will not yield to Andrzej's overreaching dominion though, he has nothing to lose, and his knife becomes the symbol of the eminent danger. It is understandable Polanski at that age, decides to side with him to outsmart his rival in the end, thanks to a telling lie ("I can't swim").But the film is not just a duel between two men, Krystyna is the key balance, in the beginning, she is introduced as an unassuming wife with an unprepossessing wig and rather dark complexion. And she is extremely disinterested in the bonding-and-clashing process between the two men, maybe she has witnessed such happenings many too often from Andrzej, and being a dab hand in sailing, one assumes she must have undergone the same tutoring from him, thus she simply has lost any interest in participation. But when she gets close the young man, the undercurrent of sexual tension starts to surface, she sultry sex appeal also slowly unfolds, especially after their song-and- poetry exchange inside the boat, she seems to find a kindred spirit. When the accident occurs, her resentment towards Andrzej explodes, and canoodling with a young man becomes her revenge to their insipid marriage (why woman can only use her sexuality as the weapon to rebel? - that's my disagreement with the film). Then the coda, when the interloper disappears, facing the crossroad, she can triumphantly take the moral high ground and keep this incident as a trumping card without the fabrication of a lie, because the egocentric Andrzej will never believe her story, aka. the truth and admit he has been fooled by the young man, a superb ending with perfect ambiguity.KNIFE IN THE WATER is a bracingly competent debut, largely shuns the disadvantages (e.g. self- absorbed pretension or becoming visually dreary) of a 3-way cast and limited settings, also it contains the accomplishment of its Jazz-fused soundtrack. But if one expects it being a taut thriller, it is not at that tempo at all, a solemn character drama is the right categorisation.

According to Chekhov, if you make people aware of a gun early on in a story, sooner or later someone in the story will have to shoot the gun. If the gun is not going to be fired, it should not be in the story. Now, knives are more common than guns, and are used for mundane purposes, such as cutting the meat on one's plate, so the rule that applies to guns cannot automatically be applied to knives. Unless, that is, it is a wicked-looking, gravity-propelled, telescoping knife with a four-inch, locking blade. When you put a knife like that in a story, then Chekhov's law applies to that weapon as well, and it is required that someone get cut with it.But no one does. Not only is this knife referred to in the title, but it is introduced early on and emphasized again and again. The tension is built up as the knife is used to play a dangerous game of stabbing between the fingers of a spread out hand. It is used again when it is several times thrown across the cabin and into the wall. And it is used to cut the halyard when the sailboat runs aground. This would be like having a gun in a movie, with people showing off their marksmanship or using it for some ordinary practical end. It would not satisfy our need to see the gun used for a more deadly purpose, just as these various employments of the knife do not satisfy our expectation that someone will be stabbed with it. But no one is.Finally, Andrzej takes the young man's knife and throws it in the water. The idea is that the young man was very fond of his knife, and Andrzej threw it in the water out of spite. But in that case, the object might just as well have been a harmonica that the young man was fond of. As it is, the fact that no one got stabbed after all the emphasis placed on the knife leaves us disappointed. Roman Polanski, who directed this movie, must have eventually figured this out, which is why Jack Nicholson got his nose sliced in "Chinatown."

This film is part of my 'Roman Polanski Collection', which also includes 'Cul-de-Sac' & 'Repulsion'; all black & white's and early in the then- genius Roman's formative career (before big bucks and Hollywood defocused him).Compositionally, it is essential to watch this in its almost square, original format, however much we are tempted to fill our modern TV widescreens with. This also helps squeeze the frame - and the slight claustrophobia that builds slowly from frame one, until the inevitable end. An orange filter (black & white filmstock, remember) on the lens creates a darkened, brooding and high-contrast touch to the blue skies and semi-bare bodies.Close-up's, using wideangle lenses creates occasional discord along the sunny summer river banks, where the loudest thing to disturb the peace is a calling cuckoo. A jazz soundtrack hovers like a busy insect, the saxophone of Bernt Rosengren weaves and plays about with us, from original music written by Krzysztof T. Komeda.The often trite and menial conversation between the young hitcher and the boat owner and his wife helps mask this growing unease. The blonde youth carries a knife. This he shows them, openly, tantalising, as if to stamp his authority. On board the tiny boat, on the water, in the water, this triangle between the trio changes and bends, softens and hardens...And, oh, it's in the director's native Polish, but that's immaterial.Hollywood movies since have indirectly and no doubt inadvertently taken both this theme and directorial touches further and beyond - and into the mainstream. 1987's "Overboard" starring Kurt Russell and Goldie Hawn being an obvious example and Phillip Noyce's "Dead Calm", with Nicole Kidman and Sam Neill even more so.