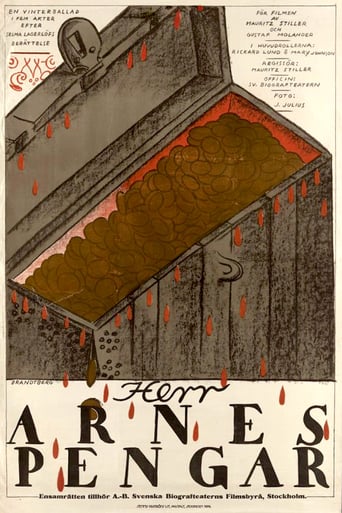

Sir Arne's Treasure (1919)

Three Scottish officers, including Sir Archi, murder Sir Arne and his household for a coffin filled with gold. The only survivor is Elsalill, who moves to relatives in Marstrand. There she meets a charming young officer- Sir Archi- and she soon understands that he was one of the murderers.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Slow pace in the most part of the movie.

Admirable film.

Very interesting film. Was caught on the premise when seeing the trailer but unsure as to what the outcome would be for the showing. As it turns out, it was a very good film.

Fun premise, good actors, bad writing. This film seemed to have potential at the beginning but it quickly devolves into a trite action film. Ultimately it's very boring.

As far as I can tell, this is the first Swedish Silent that I've watched (I'd previously been intrigued by a solitary still actually used for the DVD sleeve itself found in "The Movie", a British periodical from the early 1980s); I've seen a handful of early efforts from neighboring Denmark and the aesthetic starkness in the predominant style of both countries is pretty similar. It's also the first from Swedish master Stiller (I also own his two other well-known titles, EROTIKON [1920] and THE SAGA OF GOSTA BERLING [1924], that were released on DVD from Kino and I may very well include the latter in my current Epic/Historical films schedule); incidentally, I've only checked out and was duly impressed by two American-made pictures from Victor Sjostrom, the other great director to emanate from this country during the Silent era.SIR ARNE'S TREASURE is best described as a historical melodrama since the elements typically expected of an epic only really come into play in the scenes involving a fire early on and a sword-fight towards the end. However, one shouldn't overlook the vast and forbidding icy landscape which not only serves as an extremely realistic backdrop to the narrative incidentally, the quality of the cinematography throughout likens the film to an uninterrupted series of medieval tableaux but is very much another character in it, since the villains' flight (the perpetrators of a massacre in a household, from which they also abscond with the titular fortune) is prohibited because the sea has frozen over! Notable scenes here include: a cart-wheeling horse falling head-first through cracked ice; the youngest of the thieves having ghostly visions of one of his murdered victims (as it happens, he later falls for the girl's sister and she with him, which leads to the latter being torn whether to give her lover away or run off with him to Scotland!); the leading man ultimately using the heroine as a human shield against the oncoming soldiers; the closing procession over the ice by the townsfolk to reclaim the girl's dead body (justly considered one of the visual highlights in all of Silent cinema).The plot also effectively incorporates the element of premonition such as when the fish-hawker's usually docile canine companion senses impending doom and starts to howl, Sir Arne's wife literally hearing from miles away the preparations for the subsequent assault on her abode, the ship captain's tale of a previous case of poetic justice similarly brought on by severe weather conditions, and the heroine being led by her dead sister to the villains' whereabouts in a dream. The print I watched featured nice use of blue (for outdoor night-time scenes) and red (the afore-mentioned blaze) tinting; the newly-composed accompanying score is appropriately sweeping, albeit making use of mostly modern instruments. The main extras on the Kino DVD involve noted film historian Peter Cowie, who supplies an informative background to early Swedish cinema (where he also discusses the seminal contribution of authoress Selma Lagerlof who was behind the source novel of both this and THE SAGA OF GOSTA BERLING) and, in a separate featurette, focuses exclusively on the film at hand.

I suppose no one can understand film at all without knowing the poles of narrative.One of the dimensions is whether the world is beside the story and viewed by it. Or in some other relationship. The Swedes own one of these poles, their narratives always being buried by heavy fate and guilt about it. Its a very strange thing to see from the outside.The nature of Swedish narrative survives today, because they are so good at nurturing and presenting it. And we watch it for some reason, possibly because of the lightness of being outside the curse. The story here is of three alien murderers who decimate a peaceful household for the titular treasure. One of these thugs later falls in love with the soul surviver, a pretty girl.She feels guilty for surviving, he for murdering and both for falling in love. The meaty part of the story is toward the end where guilt drives fate and the world comes crashing down on them. The whole world contrives against them. Weather freezes. The two societies in play turn against them. Death. Death, but the deaths aren't the greatest tragedy: it is the curse of entanglement, the knowing, and the knowing that others know. And of course those others as a society are cursed.There are many dark images in this. But the key one must be one of the most memorable in all cinema. The getaway ship is frozen in the ice, Shackleton-like. The entire population of the area's women and children stream across the ice intent on recovering her, though they know she has assisted the murderer. The crew turns against their passengers believing them to be the cause of a curse. The weather.That endless stream of dark, determined villagers do indeed recover the girl, a corpse, and stream back home while the ice is dissolving right behind them. Its pretty darn entangling, and conveys the curse. No watchers, only participants.Ted's Evaluation -- 3 of 3: Worth watching.

As a title in film history books, Sir Arne's Treasure always seemed like it must fall somewhere between Die Nibelungen and Ivanhoe-- an epic knightish adventure with a heavier Scandinavian feel. In fact it's a tale of guilt and doom in the classic Swedish mode, almost a chamber piece despite its grandiose division into five acts, set in an historical setting but with some of the same distilled focus and sense of inevitability as, to pick a recent example, Cronenberg's A History of Violence. Three Scottish mercenaries (the main one, incongruously, given the jaunty name "Sir Archie"; happily his compatriots are not Sir Reggie and Sir Jughead) escape from captivity in 16th century Sweden and, driven half-mad by the winter winds and starvation, wind up slaughtering the entire household of a local lord for his treasure. Only one young, Lillian Gish-like girl, Elsalill, who hides herself during the crime, escapes-- but, being Swedish, is consumed by survivor's guilt. This being one of those stories (like Crash or Dickens' Bleak House) where there are only eight different people in the entire country, the three, newly kitted out in finery, return to the scene of the crime and Sir Archie promptly falls in love with the survivor of his depredations and starts having guilt of his own. I'm betting you can pretty much guess how that's going to work out for the gloomy couple. The initial acts of Sir Arne's Treasure take a little mental adjustment, as there's what we might call a high Guy Maddin quotient here, of over-the-top Nordic gloom-- the old crone (Mrs. Sir Arne) repeatedly shrieking "Why are they sharpening the knives at Brorhaven?" at the dinner table, the use of the phrase "fish wench" in a title, or a ship captain who believes that his ship is frozen in ice as God's punishment for some big crime he can't QUITE put his finger on.... The latter in particular shows the heavily moralistic hand of Selma Lagerlof (who also wrote Gosta Berling, The Phantom Chariot, etc.), who was good at setting up ripping plot mechanics but tended to impose a Victorian religious sensibility which you don't see in the best Swedish films, such as Sjostrom's The Outlaw and His Wife. While there's a stark, In Cold Blood-like quality to the depiction of these violent events in a remote, snowbound location, we're impressed by the dramatic quality of the events themselves, not by any human sympathy that has particularly been built up for the characters to that point. And it is easy to see why distributors in other countries succumbed to the temptation to trim the film down, as Stiller allows many of the events to play out in real time, even when relatively little is going on. It's when the film narrows its focus to the two main characters and their guilt-racked interactions that Stiller's deliberate storytelling begins to really justify itself-- the film is like the long walk to the electric chair in a Cagney movie from that point on, and the minutely detailed depiction of everyday activities not only makes the historical setting seem vividly real, but serves to cut off the possibility of outlandish movie-style heroics which will bring the story to any end other than the inevitable tragic one (which, nevertheless, contains a couple of shocking turns which wouldn't have passed muster for Errol Flynn at Warner Brothers in 1938). Mention must be made (as theater reviewers say when they can't think of a better transition) of the cinematography of Julius Jaenzon, who pretty much shot everything that was anything in Swedish silent cinema. The word inevitably attached to Jaenzon's work is "landscape," which is to say, he and Stiller and Sjostrom were all masterful at using the forbidding country they lived in to help set the emotional tone of their scenes. When they want you to feel that someone's lonely, they stick him out walking on an icy fjord and by God, he's LONELY. Also, as we all know, the moving camera as an expressive device (rather than just a way of showing off your fancy set, as in Intolerance) wasn't invented until The Last Laugh in 1924, so we can all throw out those pages of our film history books since one of the most striking things about this film is the extensive use of the moving camera throughout. Since the moving camera tends to imply the presence of the director and thus to deny the possibility of free will for the characters (which is why it works so well in things like noirs, or Max Ophuls' adaptations of Schnitzler, or Kubrick movies about unstable hotel caretakers being taken over by malevolent ghosts), it's a perfect artistic choice for this story, and one that strongly reinforces the atmosphere of destiny and doom while also keeping our focus on the mental state of characters who remain front and center within the shot, rather than on how they physically move from one place to another within a shot.

Watching 'Master Arne's Treasure' is, at times, like watching a moving gallery of pictures by Hammershoi, Kroyer or Spilliaert. The film's greatest set-piece has the anti-hero Sir Archie walking at night in a vast snow-scape. The frozen snow seems to be moving like a river away from him; in any case, its stark luminosity in the dark gives it an eerie unstable appearance; against this backdrop, Archie seems unnatural, as if his physical presence doesn't fit properly in his surroundings, like his image has been cut out and pasted ineptly onto a back projection. This prepares us for the ghostly emanation of his conscience, the young girl he brutally murdered for money.'Treasure' is one of the most shocking films of the silent era. This is partly because we are set up to identify with characters who then commit an unspeakable crime. Three Scottish aristocrat mercenaries in Sweden (reversing the Viking pillage in Britain?) are put in a military prison for conspiring against the King. Remarkably, they take this is good spirit, and spend their days in homoerotic bouts of leap-frog. This immediately endears them to the audience - a willingness to play in the most oppressive conditions. Such flippancy certainly antagonises the prison warder, who snarls and pokes his spear in at them: they manage to hold him, steal his keys and escape.'Treasure' begins as Renoir's later masterpiece 'La Grande Illusion' ends - soldiers escape from a foreign prison, tramping through the heavy snow before finding refuge in a wood-cabin. By this time, however, our heroes are starving, and play is replaced by violence as they eat and drink for the first time in months, to the horror of the wife of the house. When her husband comes home, the men are unconscious with wine, and he throws them out.Like the films of colleague Victor Sjostrom, Stiller frames his films in a natural context. But here, nature is more than simply nature, it is an embodiment of a moral order. The film begins with a snow that freezes and paralyses an entire society, and ends with a thawing that cannot take place until the crimes of the malefactors are revealed. They hope to escape to Scotland in a ship surreally stranded in sea-less ice; even when the rest of the ice breaks, it remains stubbornly immovable until the criminals are apprehended.The crime isn't shown, and we are first alerted to it by a vision of Arne's wife, who sees men sharpening their knives. This is a film full of visions (when the crime is eventually shown, it's in a vision), some of them emanations of conscience, others 'Hamlet'-like messages from the grave, revealing the murders. Christian morality plays some part in conjuring up these visions, with Arne's wife's vision a token of guilt, and Arne's treasure, said to have been stolen from monastaries throughout the country, has a negative fetishistic power.The difference between this supernatural realm and the vivid, material evocation of provincial life (dinners, dances, taverns, craftsmen, dogs etc.) is expressed in the strange, haunting imagery. In fact, the two frequently combine, especially at the end, when the death of the orphan produces a funeral cortege, a black worm of mourners slithering on the vast snow, that is both ritualistically 'timeless', strange, yet rooted in local traditions. The film's melodrama - the great suffering of its heroine, the arbitrary intrusion of brutal events, the cynical self-servingly remorseful anti-hero, the almost Kafkaesque proliferation of the military - thus becomes a kind of chilling horror story.