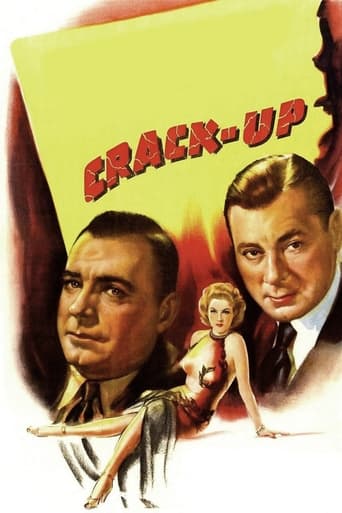

Crack-Up (1946)

Art curator George Steele experiences a train wreck...which never happened. Is he cracking up, or the victim of a plot?

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Simply Perfect

Good story, Not enough for a whole film

Fun premise, good actors, bad writing. This film seemed to have potential at the beginning but it quickly devolves into a trite action film. Ultimately it's very boring.

By the time the dramatic fireworks start popping off, each one feels earned.

In no other American film noir does art and the museum play such an important role. The main character is an art expert, and significant themes include Old Master paintings, forgeries, and even the use of x-ray technology. Granted, Fritz Lang's "Scarlet Street" (1945) involves the entanglements of an artist (Edward G. Robinson, an important real-life art collector) and mistaken identities. But in Crack-Up the institutional art world––museums, curators, and collectors—are integral to the plot. This film is also notable for representing a museum professional as a tough, noir male lead. His name is, fittingly, "Steele" (Pat O'Brien). When he powerfully hits an arcade punching bag, one character observes, "Not bad for an art critic." O'Brien's soft-spoken intensity and mature demeanor are perfect here. Similarly, the museum is shown here as a foreboding and noir-ish place, an unusual treatment; recall the bright, Technicolor San Francisco Legion of Honor in Hitchcock's "Vertigo." In one scene in "Crack-Up," the shadow of an ancient figural sculpture looms like a spider over the guilty museum director. The opening of the film, set to the shrieking tones of Leigh Harline's discordant score, shows a train speeding right at the viewer. In rapid succession we see Steele's crazed face, then his foot kicking through the glass door of a museum. Wrestling with a policeman, the pair jostles an ancient classical statue—a torso, surreal in its own way––which nearly crushes Steele as it shatters on the ground. In the background we see the well-known "Farnese Hercules" (216 AD) in a hall of classical statuary. The most telling scene for art in America at this time occurs early on, when Steele is shown lecturing in the museum's galleries. He wonders why art gives American viewers "an inferiority complex," and that "face to face with a painting we shuffle our feet and apologize." He continues: "Why apologize? If knowing what you like is a good enough way to pick out a wife, or a house, or a pair of shoes, what's wrong in applying the same rule to painting?" He then shows the crowd Jean-François Millet's "The Angelus" (1859), a hugely popular nineteenth-century painting of two peasants pausing from their fieldwork to pray. The audience makes reverential noises, but gasps in horror when he pulls back the cloth over a contemporary Surrealist painting. The picture (uncredited) resembles Salvador Dalí's "Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War)" (1936). Steele calls it "nonsense" and equates modern painters with forgers. Both are dangerous, he claims, as "good technicians with nothing to say." In the 1940s Americans were still bewildered by European modernist painting including Cubism, Constructivism, Dadaism, and Surrealism. Intriguingly, at this moment, the American Abstract Expressionists were just picking up steam. A heckler (the great Shimen Ruskin) suddenly challenges Steele. He vociferously defends modernism, distinctly foreign in his thick accent, Hitler moustache, and floppy tie. After he is physically removed, accompanied by cheers from the crowd, Steele invites his audience to next week's lecture on modern art, quipping, "Surrealists will be searched for weapons at the door." His populism contrasts with the misanthropic collector Lowell (Ray Collins), who sneers, "Museums have a way of wasting great art on dolts, who can't differentiate between trash and these masterpieces ." A wide appreciation for art—and by extension for democratic American values––is also at odds with the snobbery of the art dealer Reynolds (Dean Harens), Steele's romantic rival for Terry (Claire Trevor). Steele is soon fired from his position for addressing the perceptions of the masses. He wanted to breathe a little life into the staid museum, he says, and make art accessible for everyone. He goes too far, however, when he invites the audience to use radiography to examine Old Master paintings, which threatens to expose the art villains' scheme. The train crash can be seen as a metaphor for the war itself as well as the trauma Steele and movie viewers have suffered. Perhaps it too was a false nightmare concocted by the rich and powerful. The veteran Steele and his audience need to reengage with an understandable post- war world. His longing for truth extends to his career expertise in authenticating art, and plays out in his subsequent hunt for the authentic museum masterpieces. It also helps explain his antagonism to modern art, which doesn't resemble everyday reality. (Ironically, Surrealism aptly describes Steele's own hallucinatory experiences and the world in which he now finds himself.) And his detailed attempt to recreate what happened on the train––in essence a "forgery"-- parallels what he'd later do in the museum's conservation lab to distinguish the real Dürer from the fake one. In a scene that must have seemed very high-tech to movie audiences of the time, Steele examines pictures in the museum's lab. Comparing the original to a forgery, he observes, "It's physically impossible for two men to paint exactly the same." This also articulates the plight of the highly individualistic noir hero, who must endure his own solitary journey to arrive at an exonerating truth and justice. Steele's sleuthing recalls what the actual WWII "Monuments Men" were doing only two years before in Europe, tracking down world masterpieces and foiling the Nazi's plans for hoarding and selling them. But now the art villains are in America, and they're dealers, wealthy collectors, and museum officials. Like the Nazis, they would deny citizen museum-goers the authentic masterpieces of western culture. Overall, this film dramatizes nationalistic debates about art in a new post-war world while it attempts to engage the surreal trauma of WWII––still the deadliest conflict in human history.

Pat O'Brien is typically known for playing priests, the level-headed foil for James Cagney's explosive gangster. In other words, he's usually the least-interesting character in the film. 'Crack-Up (1946)' marks a welcome change-of-pace for the actor. No longer is O'Brien the calm, collected cleric, but a confused art critic at the end of his rope, doubting his own sanity as he battles murder and conspiracy. He perhaps isn't perfect for the role the film's lurid moments would have been even more lurid had the lead actor been able to act more deranged but O'Brien receives good supporting back-up from Claire Trevor, Herbert Marshall and Ray Collins. Director Irving Reis (best known for his "Falcon" series, though he also co-directed the annoyingly manipulative 'Hitler's Children (1943)' with Edward Dmytryk) does well to develop the film's mood, not afraid to dabble in a bit of surrealism to help translate the mental confusion and degradation of his main protagonist. There's also a little Freudian psychoanalysis in there, as was popular at the time, but the distraction it causes to the story is only an afterthought.The role of WWII in shaping the film noir style should not be underestimated. In 'Crack-Up,' combat veteran George Steele (O'Brien) remarks that his greater fear in the trenches was that his mind might unexpectedly snap "like a tight violin string." These combat-related fears are here transcribed into a society ostensibly recovering from the war, suggesting that the shadow of the twentieth century's most costly campaign was still bearing over America, a sinister spectre of uncertainty and disarray. The film's undisputed centrepiece, though it is never adequately explained, is Steele's recollection of a train crash, a sequence that almost suggests an episode of "The Twilight Zone." As Steele watches the blazing beams of an oncoming train, time appears to stand still. He sits transfixed, calm and emotionless, a deer in the headlights. In classic film noir fashion, both he and the audience know what is about to happen, but all are powerless to stop it. The train barrels towards its predestined fate, a blistering collision of light and flames. Or does it?Perhaps drawing some inspiration from Lang's 'Scarlet Street (1945),' this film noir concerns itself with the art of art fraud and forgery. The filmmakers' approach to the topic is strictly populist. At the beginning of the film, art critic Steele gives a lecture that openly denigrates the booming popularity of surrealism and "modern art," dismissing the style as being of use only to snobbish social-climbers {an unfair view, since Hitchcock had employed the services of Salvador Dali just one year earlier for 'Spellbound (1945)'}. It is these very same snobs who have planned an elaborate scheme to replace masterpiece canvasses (titled "Gainsborough" and "The Adoration of the Kings," respectively) with worthless replicas, before destroying the copies not for monetary gain, but because they're snobs, and would like to have the classic works of art all to themselves. If all of 'Crack-Up' was as lurid as the opening sequence and train-wreck flashback, then Irving Reis would have had a masterpiece on his hands. As it is, we are left with an entertaining if occasionally stodgy thriller.

**SPOILERS** Having helped expose a number of forgeries by the Nazis during WWII former US Army Captain George Steel, Pat O'Brian, got involved in the museum that he was working as a lecturer in the finer points of art. Even though the head curator Mr. Barton, Erskine Sanfod,was a bit taken back by his unsophisticated and earthy manner of how he lectured his audience. Where at time it almost lead to fists flying in his direction.It's when Steel cracked up and made a spectacle of himself one night breaking into the museum belting a policemen and almost getting crushed by a falling statue that things started really getting weird. With the opinion by Dr. Lowell, a member of the museum staff, that Steel lost his mind and needs to be institutionalized he's told to take a long vacation. With Steel calming to have survived a train wreck the night of his crack-up it becomes rather obvious, to both the police and Dr. Lowell, that the poor and confused man is either hallucinating of suffering workers burn-out. Steel doesn't take all this lying down by again going through the same motions that he did the night before. Getting on the same train and taking the same ride, to a town called Marlin. Then finding out that he indeed was not making up the story about his mental crack-up. Only that the train wreck, which he found out didn't happen, was somehow for some reason implanted into his brain! but why and by who?We later learn from a secretly on loan to the museum lawman named Traybin (Herbert Marshall), a Scotland Yard inspector of art forgeries, that things aren't exactly kosher with the art exhibits. Later Steel himself gets this cryptic phone call from his friend the museum's co-curator Stevenson, Damian O'Flynn, about a number of switch's of original masterpieces being copied and then purposely destroyed in suspicious fires. One of them is a painting titled Gainsborough, the originals ended up in the private collection of the person responsible for the destroyed copy.Going to see Stevenson at the museum Steel finds him murdered as he's spotted at the scene of the crime, by Mr. Barton, and becomes the chief suspect in Stevenson's murder. Realizing that this scheme of copying original works. At the same time having the copies destroyed in order, for whoever does it, to steal the original without anyone knowing about it. This has Steel going down to the docks where the painting that was the big hit at the museum "The Adoration of the Kings" is being shipped back to England. With Steel feeling that it's going to suffer the same fate that "Gainsborough" did some time before. With a fire suspiciously set in the storehouse, like Steel suspected, on the ship Steel saves the painting and takes it back to the museum. With the help of his friend reporter Terry Cordell, Claire Trevor, and museum technician Mary Ware, playing herself, Steel finds out through X-rays that the painting is indeed a forgery. Leading to the person responsible, an off-the-wall psycho art lover, of having Steel knocked out and then ,along with Terry, kidnapped. The kidnapper has Steel shot up with truth serum to make him talk talk about who else knows about his, the creepy and murderous lover of arts, diabolical plan. So he can have them done in like he's planing to do in both Steel & Terry.This has to be the only movie where the hero sleeps through the big slam bang final with Steel completely out of it, on the truth serum that put him on snooze control. The police and inspector Traybin come to Steel's and Terry's rescue with Steel later waking up, when all the fighting and shooting is over, and wildly throwing punches at the very people who saved his life, Inspector Traybin and police Capt. Cochrean, Wallace Ford. Yet being so drugged out of is head that he almost ends up falling on his head and breaking it.

In Crack-Up the idea is to make art expert Pat O'Brien think he's done just that. O'Brien wants to bring in some x-ray equipment to show how art forgeries can be done to stimulate interest in his lectures.Of course when you've got that going on at the museum, there's going to be someone who doesn't anyone snooping around. So O'Brien is framed with an elaborately concocted train wreck. Of course the train wreck never happened and people start thinking Pat has cracked up.The only one who believes him is girl friend Claire Trevor and between the two of them, they've got quite a task before them. To convince everyone including police detective Wallace Ford that O'Brien is still playing with a full deck and find out just why someone wants everyone to think there's a suit missing from that selfsame deck.Crack-Up is a good noir thriller from a studio which turned out quite a few of them in post World War II Hollywood. RKO always operated on a shoestring and the nice thing about noir films is that you didn't need a big budget. A good script and solid acting is usually what put over a noir.Herbert Marshall lends some British authority as a man from Scotland Yard who acts very mysteriously indeed. For those who like the noir genre, they will not be disappointed.