Good Men, Good Women (1995)

An actress preparing to play in a historical epic is terrorized by someone faxing her pages from her stolen diary; has colorful flashbacks of her affair with a now-deceased man; and imagines black-and-white film-within-a-film scenes of the movie she is about to appear in.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Reviews

Strong and Moving!

Memorable, crazy movie

Good start, but then it gets ruined

Entertaining from beginning to end, it maintains the spirit of the franchise while establishing it's own seal with a fun cast

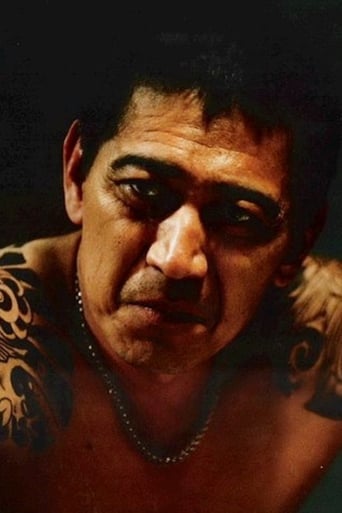

The conclusion of Hou's Taiwanese history trilogy, 'Good Men, Good Women' is not purely a continuation of the previous films' themes. It is an amalgamation of the past, present, and the connections between both. The two time periods in this film (or is it three?) are gradually intertwined to tell one cohesive story.In modern day Taipei, an actress Liang Ching (Annie Shizuka Inoh) is rehearsing for the role of Chiang Bi-Yu, a woman who traveled to China to find the Japanese in the 1940's. Liang is struggling and distraught because of the death of her gangster boyfriend Ah Wei (Jack Kao) a few years prior and because an anonymous man is faxing her pages of her stolen diary which restitute her previous memories of her time with Ah, and after his death. Liang's imaginary episodes of what the film will be like, which are for the most part shot in black and white, her immediate present, and her immediate past are all mixed together with the deftest emotional accuracy.The shots are so artistically accomplished that they are able to properly the connection of all history and past, with current personal events, and the eternal, constant binds of time. Liang's story nearly directly mirrors Chiang Bi Yu's. Both contemplate in alienation; when Chiang and her compatriots whom she enters China do not speak the language of those who they are trying to help because of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan which, for them, just recently ended. They are labeled as Japanese spies, and nearly killed, and upon the return to Taiwan they are labeled as communists. Because of the oppressive government and recent horrific acts committed by it they want to make a change to make life better. No matter how questionable and near-sighted their political views, they wanted to make some sort of change. Liang and her 'compatriots' are drowning in shallowness. Hou praises the courage of that older generation, but none of that is found in Liang's age. Yet, he appears to say, that these are the same people who go through similar experiences, and are only molded by the world around them, and therefore by history. Over time, the dream for a better future gives way to the dream for more profit because of the implications of history and the political.In the previous films of the 'trilogy', Hou searched for the relationship between life and a certain form of art. Here, it is of cinema, and therefore Hou questions his own role. Ozu's 'Late Spring' plays on a television near the beginning, and in a self-referential manner, helps represents how cinema is able to understand a people, and their conflicts whether interior or exterior. In the previous films of the 'trilogy', Hou searched for the relationship between life and a certain form of art. Here, it is of cinema, and therefore Hou questions his own role. Ozu's 'Late Spring' plays on a television near the beginning, and in a self-referential manner, helps represents how cinema is able to understand a people, and their conflicts whether interior or exterior.The regrets of the nation and the regrets of the person are all subtly laid out to dry. In order to move forward into a non-unsure and non-insecure future the regrets must be confronted. It's an eventual and long, process but one that must be done. The political invades the personal, and history's consequences affect the psychological. The implications are devastating - the present condition or 'shallowness' seemed to have been allowed to occur by the acts of the past. This is not a film that is only understandable by Taiwanese standards. It is a universal portrait of the history inherit in the present.The haunting power of the film is completely understated and will surely always linger on in the viewer's mind. It may not have the rhapsodic epic profoundness of some of Hou's other films, but it contains the grand humanism that they also have. The film is ultimately extremely encapsulating, and with Hou's formal rigour, style, and rhythm, and the expertly grounded performances it is utterly captivating, and exquisite viewing.

I was introduced to Hou Hsiao-Hsien by Flowers of Shanghai, an exquisite piece of work that spoke of a mature film maker, who had mastered his visual language. I imagine that it would be a similar experience to an introduction to Wong kar Wai or Almovodar with In the Mood for Love or All About My Mother, respectively being pieces where an good director became a great. You finish these types of films wondering where did he (the director) come from intellectually, and where is he going.Hou's style is subtle, an excellent cinematographer and picture taker, like many of the Asian films (whether this is from a common thread or by accident I don't know). He is not as overtly stylish as Wong Kar-Wai, but the shots he takes and chooses (perhaps the better adjective) are beautiful.A previous commentator called this style "cinematic masturbation", which I think is an adolescent argument. Just because the points don't hit you over the head doesn't mean they are not being made. This is a political film, dealing with a still sensitive topic. The director definitely cares about the audience. Like anything else, it's the little details that count. One of those little details is an Ozu film being played on TV in one background shot. Hou has consciously acknowledged Ozu as an influence and his style shows it. The action, so to speak, takes place within the context of the everyday events. The points being made are observed by the routine actions, and unique touches within them.The most solid point being the commonality of loss, and tragedy between two Taiwanese actresses of different generations. Both lose lovers, and sacrifice children to the events around them.The other point is the simultaneous affluence and emptiness is modern day life. The actress in the older story is based on a real person, who joined the anti-Japanese resistance in China during WWII. After this, her husband is executed in an anti-communist crackdown in Taiwan. She is both pushed along by events, but shows a determination to live her life and make decisions, This is in contrast to the other story, that of the actress playing (there is a movie within a movie), who is looking back on a life with petty gangsters, drinking and drugs. In material goods she is richer than the older actress ever was, with her upper middle class life, yet poorer in far more many ways. Both are played by the same actress, who handles the two stories well. In the Hou portfolio, I prefer this to Goodbye South Goodbye, which I felt got a little lost in fancy camera work, but I feel that this is close to Flowers of Shanghai.

It's cinematic masturbation (my term). That's not the same as intellectual masturbation, mind you. It's not that his films are pretentious, per se. Cinematic masturbation is when the filmmakers have no real desire to share their ideas, thoughts, and motives with the audience. It's all done for their own satisfaction. This is opposed to most other filmmakers, who practise cinematic intercourse, by which they call for the audience to participate in their films emotionally and/or intellectually. Hou's not the only cinematic masturbator. Jean-Luc Godard is another one, though nowhere near the level of Hou. I love Godard, but he has a tendency not to let his audience in on what his motive is (and, yes, artists, filmmakers most of all, should have a motive), especially in certain periods of his career. Tarkovsky's Mirror is another maturbatory film - it's far too incomprehensible to anyone who's not Tarkovsky. This is definitely a value judgement. Masturbation, especially on film, is extremely narcissistic. Frankly, it's unfair. Art is primarily for the audience, not the author. Otherwise, there is no point in it. Take Good Men, Good Women. It's not a bad movie, really. Certainly not Hou's worst. Its main claim to greatness is its excellent cinematography, with some sections in a high-contrast black and white and others in brilliant color. Hou also decides to move his camera a bit and film from different angles. He's finally caught up with D.W. Griffith, although he still falls back on his favorite compositions again and again. The narrative is often great - there are several great individual scenes - but it's ultimately too difficult to follow, which is the exact same complaint I had of my (currently) favorite Hou film, City of Sadness. The plot of Good Men, Good Women revolves around the life of a famous Taiwanese actress (a real person; the film is dedicated to her) and, in the more modern section of the film, an actress who is apparently going to play this former actress in a film about her life (her story is broken into two different time periods). This made sense after I read up on it, but it was really confusing when I was watching it. I assume the same actress played both parts. It's confusing because Hou doesn't want to stress anything: characters are introduced with their backs to us or when they're in shadows. How does he really expect us to recognize and latch onto his characters? He just doesn't care. No, that's not it. It's that he doesn't want us to do so: some pretentious notion that a confusing movie is an artistic one. If I were to see this film again, I might find it better. It's still cinematic masturbation. If the audience, after reading up on it or seeing it several times, then understands it, well, it only becomes mutual masturbation. Satisfying, but wouldn't you much rather be f*cking?

A film about time and isolation and loss on a personal level, and on a national level, too; the Taiwanese patriots in the film-within-a-film cannot even speak Chinese--Taiwan having been a Japanese colony since 1895--so they are strangers to the motherland and strangers when they return home. The personal story glides seamlessly into the political. Endlessly moving, and only slow if you cannot feel Hou's deep compassion and depth of understanding. Why is this film maker not celebrated everywhere?