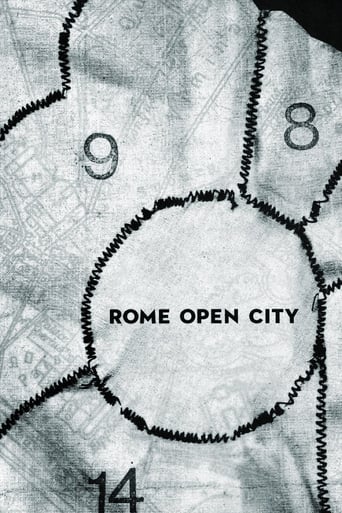

Rome, Open City (1945)

During the Nazi occupation of Rome in 1944, the leader of the Resistance is chased by the Nazis as he seeks refuge and a way to escape.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Pretty Good

Beautiful, moving film.

A terrific literary drama and character piece that shows how the process of creating art can be seen differently by those doing it and those looking at it from the outside.

Through painfully honest and emotional moments, the movie becomes irresistibly relatable

It holds an odd but very understandable significance that one of the most impacting post-World War II movies ever was from Italy. I say "odd" because Italy is perhaps the only country that started as an ally to Germany before being invaded by her very ally (not to mention the real ones) in 1943 after the fall of Mussolini. It was the failure of the fascist dream that left Italy an open country for the German invasion, with the capital Rome, as an open city.Italians saw their country literally collapsing, their fleet annihilated, the North African campaign cut short by the Allies, Italy relegated to the ungrateful small-time role in the scale of World War II, a casting error that cost so much time and efforts for Germans, notably in Greece, that its downfall caused the anger of Hitler and made it a priority to control Italy and restore the fascist regime of Mussolini (from that point, a German puppet). Despite all the resistant movements, Italy's loss wasn't just economical, but also symbolical, and what strikes in Roberto Rosselini's film is how lucid Italian people are, it's silent anger that fuel their force with vital energy. That anger wouldn't be as silent one when they'll get a hand on the ex-Duce, and I guess his fate showed how much resentment they had to vent.Nonetheless, people's anger has never be so dignified in a film without it being unrealistic, you really feel it in the general mood, even in people's way to express resignation. And the reason why this is so perceptible in the film is because Rosselini shot it shortly after the end of the war, among real ruins, and the screenplay was written while the German presence was still a fact. It's a film shot with an urge to be made and brought up at time as if Rosselini and all the actors knew they were participating to an important project, one that would show to the face of the world, that Italian were as much victims as any other countries and were not allies of the Nazi, the real Italian heart beat in the Roman streets not in a parliament.Ultimately, the film didn't end up being a powerful tribute to the sense of sacrifice and the fortitude of Italian people, it's also a magnificent and powerful tribute to all the people, in all the countries in the world that resisted the German invasion or any other invasion. The film holds a similar significance than other contemporary movies' scenes like Chaplin's final speech in "The Great Dictator" or the Marseillaise in "Casablanca". Except that it was made in more restrictive conditions. So, don't take its uneven quality, the different level of brightness and lighting as some effects to provide documentary-like realism or some artistic license. The film was made in secrecy and urgency as if it was part of a resistance movement itself.But Cinema is a world of imagery, and the film had one to offer, one that forever captures the tragedy of war and the wounds it inflicted to people. The image of Anna Magnani running, arms raised, to the truck, that is taking her soon-to-be husband, only to be shot dead by the Nazis, under the eyes of her son. It was Scorsese's "Voyage to Italy" that prepared me to this scene, one of those that impacted him the most, and for some reason, I thought it was the end of the film, as the one emotional highlight the film could have. The death of a pregnant woman, a strong mother, a future wife, whose beliefs was shaken by war's reality, was a powerful allegory of a country carrying bright hopes only to see its dreams annihilated by a barbaric force. Anna Magnani didn't play an Italian, she was Italy.And the supporting cast is a microcosm of the best and the 'worst' that war can bring, an actively resistant priest played by Aldo Fabrini and a communist (Marcello Pagliero), there is also an interestingly flawed character in Marina (Maria Michi), a cabaret dancer who prostituted herself by selling information to a female informant agent and lover, to afford some fancy lifestyle, convincing herself that she never really hurt anyone. In a way, she embodies the attitude of Mussoloni when he sold Italians' soul to the German, in the firm belief that it was the right horse to bet until Hitler, wrapped up in his megalomania decided to invade USSR. And the way, Marina Is finally treated at the end, echoed the way Italy was left and the disgraceful punishment that awaited the Duce and his followers. "Rome, Open City" is about people who incarnate the Italian spirit, oscillating between two poles, the true Italian like Anna Magnani and the wounded and weakened Italy (closer to Marina) People are torn between their patriotism, their belief in humanity and in barbarity, but all in all, only humanity can triumph, and it even inspires a Nazi officer to confront Captain Hartmann, the sadistic antagonist of the film played by Dutch actor Joop van Hulzen. He wonders why Germans dare to call themselves the Master Race, which race of lords can torture people to death, execute priests or mothers. Despite Van Hulzen's slightly over-the-top performance, you could feel that Rosselini didn't want to portray the Germans as a one-dimensional evil group either, and that foresees his future "Germany Year Zero" where he'd shine a light on the other forgotten victims of World War II: the German people. But while this film relied too much on amateur actors, "Rome Open City" is a cinematic triumph because only performances from true actors could communicate the right emotions and would have the right impact on the world.Rosselini's casting choices proved him right, and "Rome, Open City" is a masterful melodrama, a historical document and a great tribute to anonymous heroes who wrote the most glorious lines of Italian history.

In Nazi occupied Rome, German SS is hunting for engineer Giorgio Manfredi who is a leader of the communist resistance. He escapes looking for fellow fighter Francesco and finds his pregnant fiancée Pina. Catholic priest Don Pietro Pellegrini helps but he's under surveillance.It's a minor miracle that Roberto Rossellini achieved so much so soon after the end of the war. On the other hand, when Pina points to a bomb damaged building, a bomb probably did damage that building. It is considered a great example of neorealism although he had fewer unreal sets that he could use anyway. The one scene where Pina is chasing after Francesco being arrested is one of the great scenes of cinema. It is dynamic and visceral. One can really feel the action more than most war action scenes of its time.

It shouldn't work but it does. The movie is full of the most obvious stereotypical characters and formulaic situations, common to war-time movies.The story centers around Aldo Fabrizi as an unprepossessing and humble priest who helps the anti-Fascists in minor ways, but it's really an ensemble movie and Anna Magnanni, with her strong features and forceful yet vulnerable persona, plays a prominent role.Fabrizi is just fine, a flabby presence. He visits a shop and asks about the statue of a particular saint. The proprietor doesn't have that saint, but how about St. Roche over here? A beautiful representation, don't you think? Fabrizi stares at the little icon on the table without enthusiasm. Then he notices the statue of a nude woman next to that of the saint. With a barely perceptible shudder, he turns the woman's figure away from that of Saint Roche. But then he realizes that St. Roche is now staring at the woman's naked behind, so he adjusts St. Roche according to his precepts. His practical humanity makes his much less than operatic end that much more of a tragedy.If Fabrizi is the man trying to help others in distress -- he forges papers for deserters from the German Army, that sort of thing -- Anna Magnanni is the force trying to hold things together in a world that has become almost entirely unpredictable. She has a child. She's about to marry a good man who belongs to the resistance. Then the Germans intervene and that fake stability is utterly destroyed.The Germans could have come out of any flag-waver from an Allied country. First of all, the major who runs the show is effete and swishy. He's pale, his hair is gelled, and he smokes like a woman and seems to mince even when he's standing still. He has a woman agent whose job is to infiltrate the resistance and get them to squeal on each other. We meet her when someone opens a door and we see this villainous woman with deep shadows over her eyes, literally standing in a cloud of cigarette smoke. She's not only a duplicitous fiend who preys on the weak. She's a lesbian too.And then there are the scenes of torture and the speeches that go with them. "We must make him speak by tomorrow." Why? "If he doesn't speak by then he will have proved himself as good as a member of the Master Race, instead of belonging to the Slave Race." One of the German officers gets drunk and mocks the Master Race business and makes a speech. Then there's the execution, with the patriotic boys witnessing it and whistling a song of freedom for the victim.But for all that formulaic content, it's a gripping story about people of no special consequence. The performances, professional or otherwise, are convincing. In recent years many of us in the West have begun talking about the dark night of Fascism descending on America or some other country -- as if we knew what it meant.

On its initial release, Roberto Rossellini's 'Rome, Open City (1945)' was hailed for its harrowing documentary realism, sharing the 1946 Palme d'Or, and even today it is regarded as the type specimen of Italian neorealism, a movement that produced such treasures as 'The Bicycle Thief (1948)' and 'Umberto D. (1952).' The film's photographic style, which is coarse and unstylised, could certainly be considered classically neorealistic, as could Rossellini's unavoidable preoccupation with Italy's fascist history and war-time devastation. One might suggest that the film's unexceptional film-making technique was imposed upon Rossellini rather than being an entirely deliberate artistic decision; the Germans had only just withdrawn from Rome, and its citizens were still reeling from years of Nazi occupation and Allied bombing. Just as Carol Reed filmed 'The Third Man (1949)' amid the crumbling ruins of war-torn Vienna, Rossellini uses the backdrop of a fallen city to emphasise the disintegration of a formerly unified nation, now surviving only in fragmented patches of human spirit that must now be forged back together again.Rossellini's film is most often praised for its realism, and for its primary focus on the ordinary citizens of Rome. However, during the film's first half, I didn't find this approach entirely successful. Rather than centering the film intimately on one or two characters, as Vittorio De Sicae did in his two well-known neorealist films, 'Open City' instead jumps from one to another, manufacturing a sense of unity among the oppressed citizens of Rome, but also diluting the viewer's ability to identify with any one character. In this sense, the film is similar to Pontecorvo's 'The Battle of Algiers (1966),' or even Eisenstein's 'Battleship Potemkin (1925),' in that individual characters hold lesser prominence than the ideals for which they are fighting. Suggesting that the art of neorealism took several years to perfect, Rossellini also occasionally veers towards melodrama. Scenes involving the arrogant Major Bergmann (Harry Feist) establish a simplistic "us versus them" mentality, offering Germany as the outright villain in a manner similar to that of any early 1940s American propaganda film.I must admit that I found myself less-than-captivated during the film's opening half, perhaps because Rossellini wouldn't focus exclusively on any one character. The most interesting moments were those tinged with drama – a German soldier unexpectedly removes a gun from his pocket, a terrorist bomb shakes the city buildings. But if I had any doubts about the director's technique, then the harrowing realism of Anna Magnani's death, photographed as though through the lens of a bystanding newsreel camera, without any dramatic fanfare or unnecessary cinematic punctuation, convinced me of its merits. Notably, Rossellini deviates towards drama in his film's second half, but I considered this an improvement, my complete sympathy now directed towards a specific character, the dignified Roman priest Don Pietro (Aldo Fabrizi). The German treatment of captured rebels is unflinching in its hostility, including a prolonged torture session with a blow-torch, and a sombre firing squad execution as city children watch on with downcast eyes. Interestingly, Rossellini doesn't end the film with an Italian victory, as might be expected. The misery lingers; any victory could only be hollow.