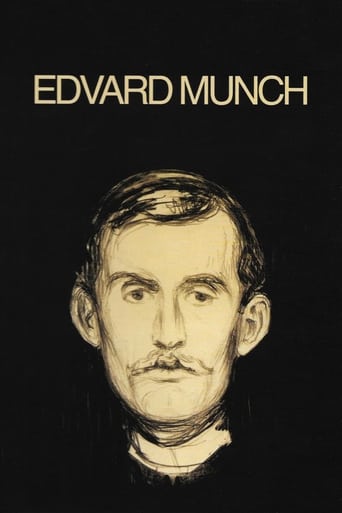

Edvard Munch (1974)

Edvard Munch's childhood is overshadowed by death: he suffers the loss of his sister and mother, while enduring serious illness himself, almost dying. At university, Munch discovers his talent as a painter. As he immerses himself in the art world, he becomes part of a cultural revolution lead by the likes of nihilist Hans Jæger.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

What begins as a feel-good-human-interest story turns into a mystery, then a tragedy, and ultimately an outrage.

The storyline feels a little thin and moth-eaten in parts but this sequel is plenty of fun.

The film may be flawed, but its message is not.

It is neither dumb nor smart enough to be fun, and spends way too much time with its boring human characters.

Since the mid-1950's the films of Peter Watkins have utilised a mix of documentary and fiction techniques to question these forms of media construct. From the historical portrayals of real, or imagined "realities" (Colluden (1964), The War Game (1965)), to science fiction dystopian visions of political systems (The Gladiators (1969), Punishment Park (1971)), Watkins has placed his cinematic eye within dramatised verite settings, refusing to conform to fiction narrative structures and the normative styles of documentary cinema. In Watkins' anachronistic cinema the characters (whether fictional or historical figures) are photographed as if the action is actually happening, and he breaks conventions further by interviewing characters, filming them in the talking head format, which eliminates the fourth wall in fiction cinema and television, and involves the viewer with the formal realities of detail. Watkins states on his website (pwatkins.mnsi.net) that Edvard Munch is his most personal film. It is certainly his most emotionally engaging, one that is not necessarily as political or prescient as previous films, but perfectly captures the emotional turmoil and strain that goes into the creative process, and particularly the ways in which events in an artists life effects the evolution of form and style.The eponymous Munch's (played, like all here by amateur actor Geir Westby) life and career is dealt with in the usual Watkins style, focusing largely on the period between 1884 and 1894, a period in which his painting developed into what would become Expressionism. It shows a young man struggling with shyness and emotional immaturity, one that when confronted with rejection from Fru Heiberg (Gro Fraas), a married woman who has affairs with bohemian types (the film constantly reminds us of the historical realities of women in 19th century Norway, who require men to live), Munch becomes jealous and possessive. The film juxtaposes these emotional moments of anguish and the tragedies of Munch family fatalities that struck the young throughout his early life, with the development of Munch's painting style. Watkins shows throughout the actual painting process. Beginning with the breathtaking picture The Sick Child, Watkins shows the anger and psychological torment that went into it. The ways in which Munch attacked to painting with knives or the non-bristle end of the brush, which created a startlingly bleak image, devoid of unnecessary details.Of course, as with anything different within an artistic medium, Munch's stripped down aesthetic was not met with praise initially, and Watkins shows the various vitriolic reactions from the art establishment and critics, both through over-heard conversations in gallery spaces, and the filmed interviews with detractors. During these moments, Munch can be seen skulking on the periphery, further exacerbating his deteriorating psychology, but this imbalance and possible fastidiousness influences his further subversion of the classical painting style - and one that would lead to German Expressionism. Periodically the narrator will place historical facts against the period portrayed, and the film is certainly as much about history (sometimes in relation to contemporary politics), as it is about an artist.The bohemian group that Munch spent time with, headed by anarchist Hans Jaeger, would openly discuss political and social issues. Even women would be part of this group, and along with the formal discussion, the "film crew" interview various female exponents, discussing feminism and the role of the female within society. Placed within this historical context, the present (at least in 1974 when the film was released) was in what appeared to be a new sexual revolution, and the feminist movement was a media convention, but in 19th century Europe, these women see what they are able to achieve living within the constraints of a male dominated society. Whereas prostitution (in the '70's it was pornography) is socially seen as immoral and degrading, these female thinkers see it as motivating, a process of female empowerment. In Edvard Munch the women are self-contained, they are individual and have power over their own lives. But this is not exclusively inclusive of female characters, it is also a film (through its documentary style) that includes the audience.Munch is the best use that I have seen of Watkins' idiosyncratic documentary style, because it is an emotional exploration, as well as a political one. The emotional aspects are embellished by the characters acknowledgement of the viewer. Throughout the film the characters look directly into the camera, addressing the audience with a glance, at times to question their own actions (should we do this?), or by including the audience in the emotional events that are occurring, you always feel included, even when those moments are incredibly voyeuristic. I at times even felt that I should not be privy to this, such was the effect of this connecting barrier. Like much of Watkins' work (and himself as a figure), Edvard Munch has been marginalised. Watkins' criticism of mass media has clearly left him out of main stream publication, and his work (whilst now gaining distribution and serious praise) is difficult to see commercially. Originally made for a Norwegian/Swedish television co-production, the film lost distribution due to the studios refusal to play it. The film did received an international release in a shortened version, but the 221 minute version is now accessible. It sounds exhausting, but the majesty and emotional connection the film presents makes it a beguiling and moving experience, and it is easily the most in depth exploration of the artistic process.www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

Munch has long been one of my favorite painters, if not my favorite, since I was seventeen years old. I love films (Angelopoulos, Tarkovsky, Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman, you name it.). Therefore, it was not a hard decision for me to forgo a particularly beautiful afternoon in the outdoors for being locked up for three hours in the AC atmosphere of a movie theater. What a mistake, and what a disappointment! Where was the editor (sorry, it was Watkins) for this film? I am amazed that director/editor Peter Watkins should so obviously confuse the television medium for cinema. The film is about one hour too long. It is repetitive, grossly uneven in its presentation of the painter's life (half-life, would be a more appropriate term). It seems that Watkins went on and on, repeating himself, and suddenly, looking at his watch, realized he had to rush through the remainder of Munch's life to finish the film. He rushed and still did not make it past 1909. Why ignore Munch, the man and his work, after 1909? But I guess this is the director's prerogative, to show what he wants of Munch's life.In general, the cinematography is good, with delicate colors. The representation of the period was well researched and comes across as authentic. The hand-held camera works well most of the time, with beautiful close-ups. In some scenes, such as the socio-political discussions in the cafes, its unsteadiness underlines the chaos of the expounded philosophy. There are even moments of greatness, such as when Munch is painting "Death in the Sickroom." Unfortunately, more often than not, the camera is shaky for no apparent reason. But there are far too many cuts, so many it makes one dizzy at times just watching, and they interfere with the narrative thread of the story. Worse, the contrivance of the cuts is astonishingly predictable -- after a while, I knew that the instant any character's eyes looked directly into the camera, the scene was going to quickly cut to something else. Geir Westby's performance, whose likeness to Munch is remarkable, is not convincing: one does not get any insight regarding Munch's internal demons, or any real sense of the artist's passion, jealousy, and repression. The dreadful environment, familial, social and political, seems practically divorced from Munch's life, as the artist appears to stand apart from it all, an outside observer. His very critical relationship with his father is hardly touched upon, except for a (too often) repeated short scene at the dining table, when Munch was still young. Munch's complex and ambiguous feelings about women in general, which shaped so much of his work, are not even touched upon, except for his particular relationship with Mrs. Heiberg (Gro Fraas). Waltkins' decision to present Munch's biography more like a docu-drama could have been rewarding, except for the fact that he was not able to integrate the historical document with the subject matter.It all boils down to the editing, which is just AWFUL. Believe me, I say this not because the film is three-hours long (Angelopoulos' and Tarkovsky's films do not exactly produce short subjects), but because when a director has nothing new to say, and keeps repeating himself, it quickly becomes tedious and boring. Most likely, the original television production was shown in three one-hour installments. Therefore, many of the numerous flashbacks were justified, not only to somehow refresh the memories of the viewers who might have seen one or two previous episodes in the preceding weeks, but also to "bring aboard" new viewers. But in the continuum of the film, these same flashbacks become useless, even counter-productive, unnecessarily weighing down the viewer with back-story.Please note that I did not follow many of my fellow spectators who left the theatre early. I suffered through to the ending credits.

Probably the most powerful biography of a painter on film with Tarkovski's "Andrei Rublev" and Pialat's "Van Gogh". The way Watkins handles the narration of his film and of Munch's life and art is simply amazing. A perfect example of life as art and art as life. The commentary is never redundant with what is seen on the screen and like the works of Munch, the shape of the movie is like a spiral, where scenes come back over and over, in a repetitive manner, like the paintings/carvings of Munch, who often drew the same subjects. It makes you want to see more of Munch's works as well as other movies by Watkins. Definitely worth being seen more than once.

This is one of the most moving, experimental films I have ever seen. Peter Watkins' political understanding of the times and his compassion for the struggling, alienated artist is superb. He has a unique method of linking the present to the painter's traumatic past, namely the deaths of his mother and sister from tuberculosis, when he was a boy. The camerawork and close-ups of individual faces is excellent. Munch's grief, when he loses the woman he loves, leads to his best works and a premature death. No other director has made a film about the inner and outer worlds of an artist as well as this. I highly recommend the film.