The Hour of the Furnaces (1968)

An impassioned three-part documentary of the liberation struggle waged throughout Latin America, using Argentina as a historical example of the imperialist exploitation of the continent. Part I: Neo-Colonialism and Violence is a historical, geographic, and economic analysis of Argentina. Part II: An Act For Liberation examines the ten-year reign of Juan Perón (1945-55) and the activities of the Peronist movement after his fall from power. Part III: Violence and Liberation studies the role of violence in the national liberation process and constitutes a call for action.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Powerful

If you like to be scared, if you like to laugh, and if you like to learn a thing or two at the movies, this absolutely cannot be missed.

There is, somehow, an interesting story here, as well as some good acting. There are also some good scenes

Exactly the movie you think it is, but not the movie you want it to be.

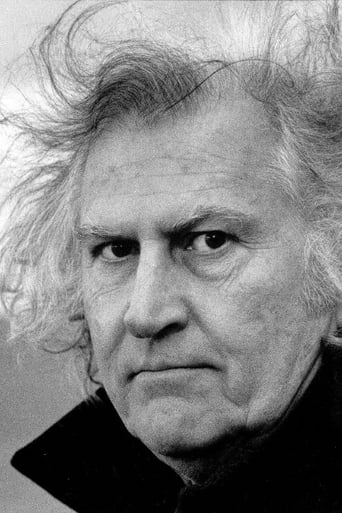

Fernando E. Solanas with Octavio Getino made a documentary about neocolonialism in Latin America. It's a very evocative film, a call to arms. It can be seen as a series of various themes of the revolution. The original version is 4 hours long clearly divided into three independent parts: I Neocolonialism and Violence (95 min), II The Liberation Struggle (120 min), III Violence and Liberation (45 min). But very often in Europe and the States we only see the first part, which might give a little limited picture of the subject - but I can't say for sure because I have only seen the first part in theaters.The first part Neocolonialism and Violence is the second longest and divided into twelve sequences: History, Earth, Everyday violence, Port city - Buenos Aires, Oligarchy, System, Political violence, Neorascism, Dependence, Cultural violence, Ideological war and Alternative option, which ends up filming the face of the dead Che Guevara for 5 minutes.The Hour of the Furnaces was very unique and original but on some level it reminded me of Santiago Alvarez's 79 Springs (1969), which proved that agitation can also be very intellectual. In the same way The Hour of the Furnaces is a synthesis of agitation and poetry. The art of editing and the use of montage is brilliant - the director clearly knows how to use this theory Eisenstein and Vertov created and defined.Through montage Solanas achieved cinema poetry he managed to create mental associations and allegories by showing suffering cows and the imperialistic American mass products. I had already seen impressive films about colonialism and imperialism - to mention a few; Moi un noir (1958) about the imperialism in Ivory Coast by Jean Rouch, The Song of Ceylon (1934) about the colonialism in India by Basil Wright and Les statues meurent aussi (1953) about colonialism in Africa by Chris Marker and Alain Resnais. But none about the neocolonialism in Latin America the intention of The Hour of the Furnaces was clearly to wake up the people from the lethargy they were in. To show the reality and make the revolution happen. Obviously the filmmakers got there. Because I personally didn't know much about this and it was quite shocking to see it - a very eye opening and thought provoking experience.The Hour of the Furnaces is perhaps the greatest and most intelligent agitation can be. It's a realistic description of the neocolonialism in Latin America and about the revolutionaries. It is not just aimed at one group of people, the film manages to speak to all the people. Solanas shows us a society where the price of human life is forgotten, where people do more work and make less money and the world with no human value.

I think any analysis of this film should take into account the context in which it was released. In Argentina in the late 60's there were tremendous injustices inflicted upon the people. Argentina's teenage industry was being undermined by the unrestricted entrance of foreign capitals and products. Factories started to "rationalize" the personnel, workshops were closing, unable to compete with the multinationals that were landing in our fragile economy. This was not new at all for a country which has not yet fulfilled his economic independence, but the signs of underdevelopment were getting more and more evident in a country which has historically considered himself more European than Latin American. Whatisworse, democracy has become an utopia in a country where its major party was banned, and the minority parties which were allowed to rise in power after limb-democratic elections were quickly overthrown by the constant military coups. Argentina lived from 55-83 in a virtual State of Siege where all political activities related to the major party (Peronist Party)were fiercely persecuted. These regime did not hesitate to assassinate and imprisoned popular activists. So the Argentine people arrived to a sideways in those years. Either stay silent and tolerate the injustice, or raise their voice in protest. To raise the voice in those times involved persecution and most probably, death. So there was a new choice to make. Either protest and get killed or to protest and defend oneself. Argentine people were not thirst for blood, they were sick of injustice and were willing to fight for a better existence. The film is not a call for violence, it is a call for understanding, a call for conscience. the movie is the voice of the silent workers fed up with treason and exploitation.

Argentinean Fernando Ezequiel Solanas and Spaniard Octavio Getino were two outstanding activists of Latin American cinema. They took different routes (Getino was the philosopher, writing about cinema, economy and politics), but in the 1960s they collaborated on one of the most important manifestos of the "New Latin American cinema", known as "Towards a Third Cinema", and together they made "The Hour of the Furnaces: Notes and Testimonies on Neocolonialism, Violence and Liberation", one of the major works of Latin American documentalism, which they defined as a "cine-act" to inform, beyond the entertainment factor. If one of the three parts that comprise this work has to be seen, "Neocolonialismo y violencia" (running 90 minutes) is the key part and the mandatory section for the specialist to see. This first part is a document with particular annotations, tinted with manichean, dogmatic or contradictory position, inherent to its Peronist proclivity; a document created in a very specific time, when several Latin American countries were living moments of intense political, cultural and social unrest, in their struggles against imperialism. However, it is as striking today as it was in 1968, because of its stylistic devices, recurring to Brecht's alienation effect and the audience's interaction (in some points of parts two and three, intertitles ask to stop the projector and start the debate), but above everything else, because of its lucid approach to neocolonialism in Latin America through a methodical analysis of a particular national history, including the complicity of local oligarchies. This is also the documentary that ends with a long shot of the lifeless face of Ernesto "Che" Guevara filling the screen.

First of all, I must say I only saw the first part of this film which lasts about 90 minutes. According to the people who were presenting it, the first part is the most accessible to modern, non-Argentine viewers.This film is a lengthy diatribe against the smothering influence of European powers in Argentine cultural and economic life. The anger of the film makers was very effectively expressed by the film's rapid fire pacing, its fiery narration and its harsh, thundering soundtrack. The soundtrack was the strongest element, and its relentless pounding really drove the film maker's points home.This film seemed less like a documentary than a filmed version of a revolutionary pamphlet. The single mindedness of the views expressed and the solution proposed, namely violent revolt, seemed immature and insufficiently reasoned. The views expressed seemed more inspired by bloody minded hatred for outside meddlers than sympathy for the oppressed and marginalized native Argentinians. It was very much a "shoot first and ask questions later" attitude. This is not the sort of attitude that I would want to see shown by my leaders if I were an Argentinian.I suppose much of the bitter hatefulness of this movie can be understood by considering that it is a reaction to very oppressive censorship. Such a movie is acceptable as a preliminary blast against the oppressors, but one would hope that calmer, clearer heads would prevail afterwards. The attitude of the film makers here, in this film, really borders on the unhinged, the demented.