The Belly of an Architect (1987)

The American architect Kracklite arrives in Italy, supervising an exhibiton for a French architect, Boullée, famous for his oval structures. Tirelessly dedicated to the project, Kracklite's marriage quickly dissolves along with his health.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Pretty Good

How sad is this?

It's a good bad... and worth a popcorn matinée. While it's easy to lament what could have been...

All of these films share one commonality, that being a kind of emotional center that humanizes a cast of monsters.

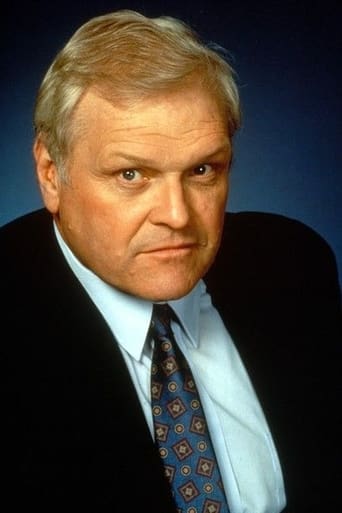

It is a crying shame that not many amusing films about human anatomy have been made.British film "Belly of an architect" fills this artistic vacuum by being an outstanding film about architecture,belly and infidelity.In some ways,British cinema author Peter Greenaway must be hailed as a genius director especially for the manner in which he has linked a part of human body with a creative art.His film is a vivid description of an artist's progressive descent into hell.This is one of the most important parts played by American actor Brian Dennehy.While watching this film,it can be surmised that some of the viewers would surely be tempted to link hypochondria with an artist's descent into hell.However, dedicated viewers would be surprised to learn that Hypochondria is not this film's main theme.This is a film about boredom,infidelity and general nature of uselessness.This is a film to watch if one wishes to explore richness of British cinema especially films directed by Peter Greenaway.There is really good photography by veteran French DOP Sacha Vierney.Peter Greenaway has also shown some good views of Rome.This might help viewers to ascertain how Italians view art and American people.From a bored housewife's point this is a film in which no one opts for a direct killing.This is the reasons why strange conditions are created in such a manner that people automatically get frustrated and decide to kill themselves.

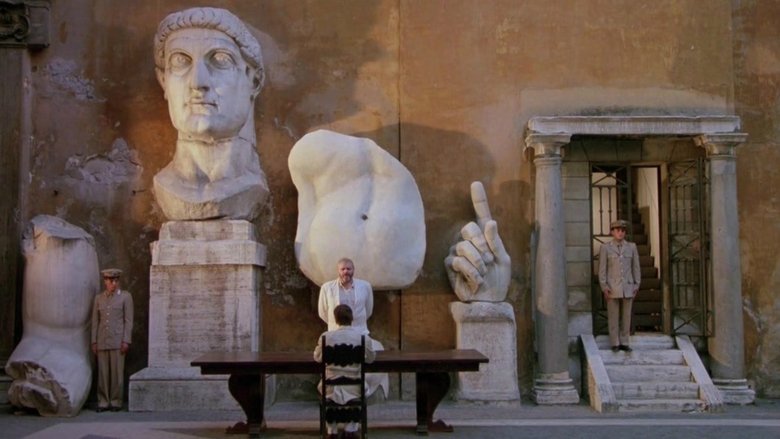

I always know I can turn to Greenaway for nested worlds. He's one of few who can - not always mind, but the few occasions are precious - align the notions of image, how they project outwards to form what we know of reality - an empty field of anxious, random forces tossing us around - and the interior springwell from where these images flow out and which reveals ourselves to be in control of them. The play is usually given to us by some sort of fiction passing as real, or a charade within another, a story within itself, so that we may be directed from the confines of the narrow frame into a broader view that includes it.The idea is especially powerful in the context of architecture, that we use form to project outwards a set of ideals but, having understood ourselves eventually circumscribed by structures that describe us, we can then use them to describe the inner landscape.So indeed, we stroll around one such interior Rome, where earlier decadence or glory, or masks thereof, greeting us from marble balustrades and rows of pillars reflect inside. A city so ornately decorated and cast in stone, as though man would outlast his follies.Into this comes an American architect - the man whose folly is to build things that last - to stage an exhibition for some obscure French architect who died 180 years ago. Italians are not too happy that he hasn't picked one of their own, but they oblige to finance nonetheless.There are two broad ideas that Greenaway is careful to lightly caress, tease out their potential implications, but finally circumnavigate. The film would have been lesser had it settled on either, or is perhaps greater for encompassing both.One is the doubling; the architect begins to imagine himself as his older counterpart, writing letters to him in the form of private confessional; then begins imagining himself as emperor Augustus, trapped in the same ploy of marital infidelity and murder. He replicates these stories around him. So these people overlap and are mirrored with bellies, bellies aching with the toll of creation. At this point you may think it is all going to be another film about the creative person losing himself in the mind, merging life with narrative.The other is, as always with Greenaway, about all this as doubling for the making of the film. It's a film-within device, make no mistake. So the visionary artist is increasingly frustrated by lackeys, ignorant money-men, virulent antagonists scheming to usurp him; energy is wasted in duplicitous dinner parties and idle, but always more or less venomous, chit-chat, until eventually finds himself embittered and alone in his own set.But it is not merely about the price of genius, or a satire of the contemporary civilized arena that it has to bleed into.Look for the scene with his doctor in front of the busts of emperors; each bust a face and story, one decadent and evil, another perhaps famed as wise, but all inadvertently gone. A little further down is a bust without name, it could be anyone's, and whatever story will be inscribed upon it, it's again only destined to join this gallery of fiction. It is important to see these follies, but more important to see the continuity.So it is this acceptance on the part of the architect, the man who builds things not only to last but to be beautiful in time, of the turn of the wheel, decline through rebirth. It is powerful stuff to see; the scene in the police station near the end, where he is simply asked name and age, whether married or not. He is free to go then. He has been jotted down in the ledgers.The final scenes in the exhibition center echo with this casual dismissal of a life lived, a casual but sweet, relieving it would seem, departure after so much grief with nothing to weigh on the shoulders. He attends the exhibition, the work of a lifetime, from the balustrade above, from the vantage point of not being involved anymore. Everything looks like a small ceremony from there. So this is the nested world that matters; not the exhibition, but the creative life on the ego-redemptive journey through life at large, purging itself of itself, after the painful struggle to master the world building pantheons finally submitting to be the mastered world, transient, as it comes into being and goes again.As he goes, new life is born down below - and plays, again and again it would seem, before the colossal marble structures.It is perhaps the ideal Greenaway film; the self-referential tics are all present, the framework ornate, but instead of chaotic it is all mastered into a pillar that supports, unifies vision. The architect - on more levels than one - coming to terms with the architecture of a transient life.

Dreamlike, beautifully shot by great Sasha Vernie and equally disturbing (as all Greenaway's movies are), "The Belly of an Architect" (1987) tells the story of an American architect, Stourley Kracklite (Brian Dennehy) who came to Rome to work on the exhibition dedicated to the French architect of the 18th century, Etienne-Louis Boullee (1728 - 1799). Stourley brings with him his much younger wife Louisa with whom is passionately in love. Everything looks good for him he's got a project of his dreams to work on, his wife is with him, and his Italian colleagues seem to be supportive and exited about the exhibit as much as he is. Soon, though, the things begin to change and look rather grim Stourley's pregnant wife enters the affair with a younger man, the work does not move as quickly as it was planned and on the top of all, Stourley gets sick and perhaps more seriously than he thinks.When I watch Peter Greenaway's films, I know they will be a feast for brain, eyes, and ears his films consist of frames so perfectly composed that you want to capture every moment of them and exclaim like Goethe's Faust did, "Stay a while! You are so lovely!". The music in his films matches the visual beauty perfectly, and his outlook at the familiar world is always original and arresting even if it lacks warmth and sentimentality. "The Belly of an Architect" is all that: it is filled with symbolism and references to history, Art, and anatomy. It is also a social satire on difference between cultures but it is a compelling and moving story of one man's descending to chaos, hopelessness, despair, and eventually death. This is the first Greenaway's movie since "The cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover" that made me feel compassion for its protagonist. I believe it is due to the incredible performance by Brian Dennehy - quite unusual name for a Greenaway's film but was he great as the architect of the title. Dennehy creates a character that is not likable as the film begins but heartbreaking and tragic by the end.8/10

Starring Brian Dennehy, an unusual actor for a Peter Greenaway film, as Kracklite, an architect, a career we don't often see explored in cinema, Greenaway's 'Belly of an Architect' is somehow bigger and more emotionally ambitious than most of his other works, which lack human resonance. In his other films, the characters are uniformly British and so Greenaway's coldness and archness toward them is indicative of a general misanthropy. Here, it's aimed squarely at Romans, whose loose morals and carnivorous practices contrast with the enormity of Kracklite's ego and generosity of spirit. His stomach is being eaten away by some unknown illness or cancer, and this serves as a metaphor for his ego being eaten away by the carnivorousness of Roman culture. His wife, his identity (which is a vicarious one, given his devotion/debt to his idol, Bouleé) and his work are being repossessed by the conquestful Roman carnivores who aim to destroy him simply for the material gain of taking what is so ostentatiously his. But his devotion to Bouleé, his need to make Bouleé's work more widely known, is not a singular or altruistic act; the exhibition he is organizing will make Bouleé more commercial and accessible, but it will also be an addendum to his own career, a manifestation of his ego. His diary is written in the form of letters to Bouleé, to whom he is almost praying as his own personal God. And his devotion to this God is not a selfless one, since Bouleé is so inexorably an element of his own identity.Rome and its buildings are given a golden, postmodern glow, their clarity enhanced by Wim Mertens' musical score, which adds its own sunlight to the proceedings. But the sunlight that glows throughout Rome and permeates the aura of the film is an impersonal one, an indifferent one, as ancient as the ruins of Rome, which our Roman characters observe have been more useful and influential as ruins than they were prior. "They're better as ruines," a character observes. "Your imagination compensates for what you don't see, like a woman with clothes on." The Romans are depicted here as carnivores (and the word "carnivore" is used multiple times) who not only want to devour and repossess, but want to strip. Brian Dennehy's performance here is indeed stripped, larger than life, fiery. He explodes on screen, bringing the film into another realm, introducing emotional dimensions not often seen in the films of Greenaway; and in this, the film has a power that inhabits the movie's symmetrical form (mostly every shot is symmetrical), its architecture, and threatens to destroy it. The coldness that is typical of Greenaway, that architecturized godlessness, is at war with fiery human passion in all its flawed nakedness.Greenaway's movies, in their arctic wit and obsession with symmetry, are cinema as architecture more so than storytelling, so 'The Belly of an Architect,' contrary to the claim by many that it's his most mainstream and therefore weakest work, is perhaps his most appropriate film, and maybe his best