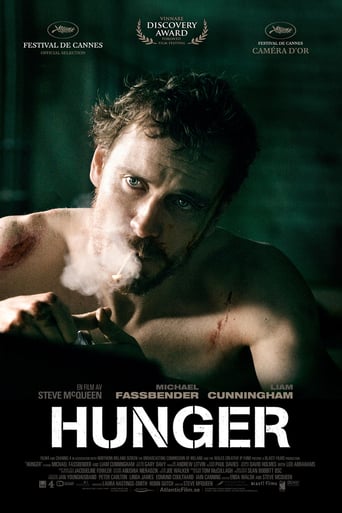

Hunger (2008)

The story of Bobby Sands, the IRA member who led the 1981 hunger strike during The Troubles in which Irish Republican prisoners tried to win political status.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Just what I expected

While it is a pity that the story wasn't told with more visual finesse, this is trivial compared to our real-world problems. It takes a good movie to put that into perspective.

Exactly the movie you think it is, but not the movie you want it to be.

Blistering performances.

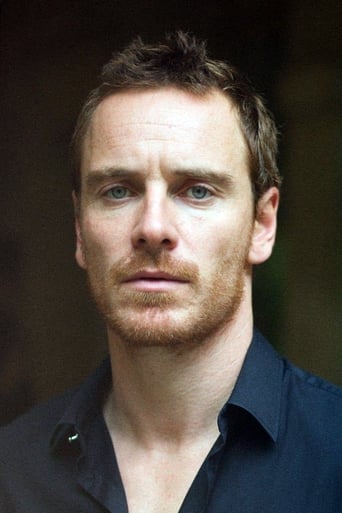

Consider how Steve McQueen captures a character's morning in his debut feature film Hunger. He uses extreme close-ups to gradually unveil the strict routine of getting ready to go to work. The man is silent and efficient; he tucks a napkin into the folds of his shirt like a scientist slipping into his lab coat, and observes the food as more or less one of the many requirements of the experiment. We see him silently check under his car for a bomb, and nervously glance along the empty street. A POV spies on him from behind a curtain - it's his wife, who we realise must also undergo the same agony each morning, gripping her hands tightly together as he turns the key in the ignition. He is Maze prisoner officer Raymond Lohan, who sits alone in the cafeteria and does not indulge in locker room talk. What we observe is the learned, robotic discipline of a man who cannot afford to make mistakes or become emotionally invested in his work. McQueen offers another close-up of Lohan against a mirror, a face straining in pain. And only after have we become invested into his life and curious of his struggles does the film reveal bloody knuckles, and the revelation that another person somewhere else is in much more pain than he is. By the time McQueen returns to the same sink half an hour in, our feelings and sympathies have been changed because of what we have witnessed. For years before hitting the big screen McQueen made short films, many of which were looped as exhibits in various art galleries and museums. These roots are evident in Hunger, which eschews classical narrative and storytelling and instead opts to wade into the vague and often ill-defined territory of art film, preferring enduring images over explanations. Much of the first half of the film is filled with moments that could define it: the camera swooping over the sh*t-stained walls and finally descending onto the dishevelled figure of Bobby Sands, the slow, silent burn of a hallway leaking puddles of the protester's urine, the way the world slows down as a wall separates the beatings and a lone, sobbing prison guard, singled out for his youth and naivety. It's brutal, senseless violence, as evidenced by the wall of sound and pain that the prisoners are marshalled through, or the way water droplets hit the face of the lens as they are forcibly bathed. But as much as McQueen strives for realism with his hand-held and guttural sound design, he can't help but aestheticise until it's not merely tragedy, but grandiose tragedy. Sands has had plenty of time, and turned his own faeces into a swirling piece of art. A hole in the cell window grating allows a shaft of white light to peek through, and a prisoner marvels at a fly that crawls upon his fingertips, not merely an insect but a symbolic representation of the freedom he craves. The treatment of the final days of the martyr Sands outdoes all these. The most discussed segment of the film are the two unbroken shots of the conversation between Fassbender and Cunningham, and for good reason. Like the better cinematic priests (think Brendan Gleeson in Cavalry, or any of the religious figures in Doubt), Cunningham is inserted not as a moraliser but as his own character, able to understand the complexity of the situation and offer his own perspective. Before they descend into rhetoric they engage in small talk, as Moran teases (he doesn't object to the sacrilege of the bible for a smoke either), and McQueen is able to make us understand that this is a routine they have endured before, and that through the seventeen minutes they always come to the same impasse. Moran sympathises and does not simply condone; although Catholic doctrine states that suicide is a sin, he is more interested in Sands' end goals and well-being. Forget the eternal suffering of your soul, what about your physical body and mind now? The pair are so well-versed in the exchange that they are on the verge of cutting each other off and jumping to the next line, or at least Cunningham's Moran is, sensing that his time is running out to save this man's life. Although much has been said about the symbolic meaning behind Sands' story, the visible result is that it paints him as a man of utmost conviction, able to shoulder the burden and responsibility of darker deeds for the greater good of others. But a story simply isn't enough. There is a lot more context here, and the film deliberately avoids engaging with the historical and political baggage of the situation, diminishing it to personal struggle. It depicts the increasingly fragile state of Sands' body, dissolving untouched meal trays onto each other, shoving the camera up close and asking us to cringe and avoid averting our eyes. McQueen doesn't filter Sands' last stand through the lens of a wider protest, or evoke the desperation of a group of men resorting to their remaining weapon, but reduces it to body horror, and renders the iconic visage of Sands into a withered metaphor for determination and conviction. Fassbender may be good at this, but he lacks the symbolic connection to the thirty thousand Irish residents who voted him into the Fermanagh and South Tyrone parliamentary seat during the hunger strike, so he's merely a physical body in decay. Not that this deters McQueen, however. In his close he all but denounces the stylistic precedent already established, and resorts to burying Sands in myth, superimposing flights of birds over his body, and bathing him in angelic light to transform his plight into rapturous martyrdom. No doubt Cool Hand Luke and Michelangelo's Pietà were consulted. And finally McQueen stumbles clumsily into formalism, revealing a younger Sands surveying the piety of the almost deceased older Sands, yet it almost seems to be a look of pity.

Although Hunger was Steve McQueen's debut feature film, I watched Shame which was his 2nd film before Hunger. His style looked unique and brutally explicit, but at the same time delicately artistic with the right amount of reticence to challenge the viewer. I was so glad to find the same positive attributes about his directorial work in Hunger too. He is one of the most recent directors whom I can easily call an auteur due to his signature style.Like Shame, Hunger is also at times a very tough film to watch. McQueen leaves absolutely no stone unturned to depict the brutal realism connected with the subject matter. The film on the surface is about the well known IRA member Bobby Sand's revolt and the hunger strike that he declared to force the British Government to grant the demands of the IRA. But to be honest, the film has very little to do with the politics of the matter. McQueen is more concerned with the people caught in the midst of this traumatic stalemate situation. He is concerned with the psychological and of course the physical effect this situation has on these characters. I liked the fact that McQueen effectively remains unbiased and neutral throughout the whole film. This neutrality is accentuated by the fact that he uses the perspective of different people belonging to either side of the tussle in the screenplay. So not only do we get to live these traumatic days from the point of view of Bobby Sands and his fellow prisoners, but also from the point of view of prison guards and riot officers. It is shown that the ones executing the strikes might have had to endure physical pain and torture, but the ones on the other side had to endure psychological torture too as well as the lack of security in public. One of the most admirable features of Hunger is the use of silence in the film. Almost 75% of the scenes are silent or with very little dialogue. McQueen allows the visuals and facial gestures of the actors to convey a lot in many scenes in the film. The makeup of the actors and production design are also meticulous with a lot attention to detail. The prison cells look as realistic and as dirty and grim as possible. The prisoners look equally worn out due to the harsh treatments handed out to them. The makeup is so detailed that even the teeth of the prisoners look worn out and decayed.There is a famous one take conversation scene in the film that goes on for about 15 minutes. The conversation in this scene is almost as serene as a Symphony. It starts out on a light note, then becomes heavy and heated and then ends almost poetically. When a single take scene which continues for such a long while works so well, all you can do is appreciate the acting and the writing that has gone into it. Talking about acting, Michael Fassbender sets the stage on fire with a jaw dropping performance. The film's subject matter and the content being too bold for the consideration of the Academy is the only reason I can think of which can explain why Fassbender didn't get an Oscar nomination for this role. He becomes the character of Bobby Sands through absolutely brutal method acting. He is unbelievably good.Overall I loved the film. The only sort of gripe that I have is with the ending. Although I liked the ending, but I wanted it to be a bit more effective and memorable. But having said that, it is a minor gripe. Hunger is not for everyone, it is disturbing, it is visually explicit and Mcqueen demands patience and attention from the viewer. But if you are prepared for all this, then you are surely going to have a rewarding experience.

A remarkable feature debut from director McQueen. It was only after I had seen, 12 YEARS A SLAVE, that I tracked down this film, and I was not disappointed. McQueen is a thinking persons director, he is not a director that makes every scene so blatantly obvious. You have to work for it and the rewards are rich in pure mental stimulation. What is also rewarding is the performances. Not only is Fassbender outstanding, but the support cast as well. The acting is paramount as it brings realism to the hideous conditions in a world we all fear, that of the Irish Maze Prison during the civil conflict. McQueen does not shy away from the politics that tore a nation apart, nor does he tone down the harrowing violence within the faeces smeared walls. Be patient, and the film will reward you. If you are looking for entertainment, then please go elsewhere. Now time to track down McQueen's 2011 movie, SHAME.

The Film is like an oratorio fort he death of Bobby Sands in a British prison in Northern Ireland in 1981 after a sixty-six day hunger strike. He was only the first one to die in a series of nine and it took nine lives to be wasted for the British government and Margaret Thatcher to yield on all the demands of the prisoners except the status of political prisoners.The film does not rewrite history and we are supposed to know this most abominable episode of the inglorious war in Northern Ireland. The British had no future there but after this dramatic event the British had lost any moral or political claim in Northern Ireland which was both part of Ireland and not British at all, except as a brutal colony.The film just gives us a believable vision of this horror: the refusal to wear prison uniforms, hence the locking up of the prisoners in absolutely unbearable semi-isolation with nothing to wear but a blanket, thence the refusal to wash and the frightening painting of the cells by the prisoners with their own excrement. Then they had to be taken one by one to be forcefully shaved and washed up in a bathtub with a lot of violence and beating up. The only right they had was that of common criminals: a visit by relatives every so often, or rather every so rarely. Then they accepted to put on a pair of black trousers: the only moment when they were dressed. The hunger strike on March 1, 1981 was the most drastic decision and the film tries to listen to Bobby Sands' arguments when he discusses them with his priest. We have to listen to those of the priest too, essentially that it was vanity that moved them because they were looking for martyrdom and if they died, the priest said, it would only be suicide. And we know what that means in the Catholic Church.Then the visual depiction of Bobby Sands' death is very graphic. The hatred of some of the nurses and auxiliaries was obvious, including their having UDA tattooed on their fingers so that the prisoners could know where they stood and this UDA capital letters were tattooed on the hitting phalanxes of the fist. The violence was not only real but also symbolical. In fact the film contains little dialogue because the objective is to show the humiliation and the violence and nothing else on one hand and the resistance on the other hand. On one hand you had animals of prey torturing their prisoners. On the other hand you had prisoners reduced to be animals and building their dignity in pushing it to the end of the line, to death if necessary and it was necessary for nine of them.An extremely disturbing film showing how low the British fell in this war and they even stooped too low to be able to conquer anything. They just failed and were defeated.Dr Jacques COULARDEAU